By Sarah Goldin, Ph.D. Partner and Director of Qualitative Research

When meeting new clients I often summarize my career/learning journey to GLP as “Research scientist turned science educator turned education researcher”. Representing a melding of these interests, the June 27, 2022 New York Times article “CRISPR in the Classroom” really struck a chord.

As a doctoral candidate studying Genetics and Development in the late 1990s-early 2000s, I worked in a lab that researched the function of a family of genes called the “T-Box genes” using mice as a genetic model. One key avenue of inquiry into the roles of these genes was to create “targeted knockout” mice – i.e. mice that entirely lacked a specific gene – and then observe how the absence of that particular gene impacts development of the embryo. And so I spent four of my six total years of graduate school trying – sadly, unsuccessfully – to make a targeted mouse knockout for the gene Tbx 2. You'll have to trust me that my lack of success was NOT because of gross ineptitude on my part, but rather due to the vagaries of the very complicated and sensitive series of experimental steps required to make that happen. Fortunately, a later graduate student and colleague finally succeeded in generating a Tbx2-knockout mouse (if you are inclined, feel free to check out Zach’s work here!).

So what’s my point?

The very first “knockout mice” – mice containing the first targeted deletion of a specific gene – were generated in 1989 (see e.g. here and here). That the technique could work at all, no matter how problematically or inefficiently, marked a sea-change in the study of genetics. Excited by the possibilities, scientists throughout the 1990s and 2000s struggled to create targeted mouse knockouts for their gene of interest one gene at time – and doing so required an extremely high level of technical expertise and sophisticated (and expensive!) equipment and supplies. 18 years later, Cappecchi, Evans, and Smithies were awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for their discoveries of principles for introducing specific gene modifications in mice by the use of embryonic stem cells."

Fast forward to 2012, and the advent of the CRISPR technique. CRISPR was first reported in a June 2012 article in Science magazine by Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna (and others). Only 8 years after this first publication, Charpentier and Doudna were awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for the development of a method for genome editing” using the CRISPR technique. Perhaps the “Nobel Prize fast track” says it all, but it is impossible to overstate how much of a “game changer” CRISPR was for the study of recombinant DNA and genetics. That which previously took painstaking years with a fairly high failure rate could now be accomplished far more reliably in a highly compressed timeframe and in a much more resource/cost-effective way.

Even faster forward to 2022, and now targeted gene editing can be accomplished by your typical high school student in a matter of days using commercially available kits from any of a number of educational supply companies, including BioRad, Carolina, Rockland, and Innovative Genomics. Holy moly!

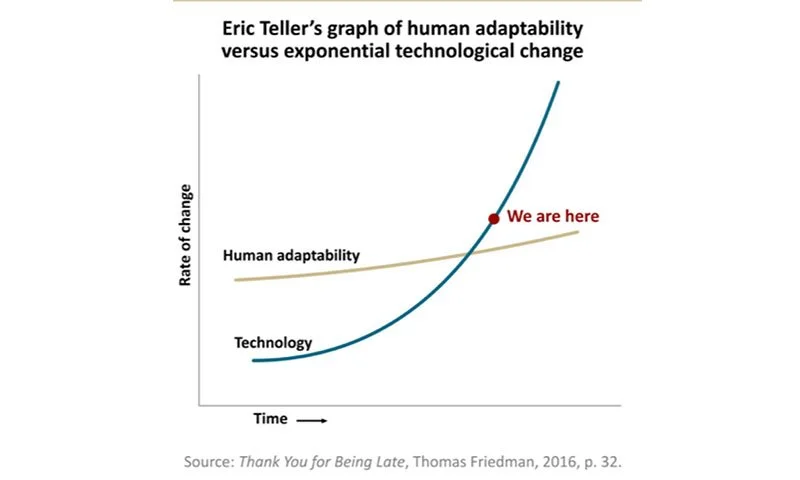

Granted, students using these kits are working with fast-growing relatively simple bacteria (not mice), but the essential point (and why the article “CRISPR in the Classroom” made me say “Wow!”) is the accelerating pace of change exemplified by this one specific scientific technique. And not just acceleration in the timeline, with profound advancements happening in shorter and shorter intervals of time, acceleration in every aspect of the technology – how long the technique itself takes to complete, decrease in cost of materials, and decrease in expertise required to successfully use the technology.

When GLP works with schools we explicitly name this accelerating pace of change as an ongoing condition - otherwise known as VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity). Whether we’re talking about advancements like CRISPR or disruptive events like COVID, we have long asserted that all organizations must intentionally cultivate agility, adaptability, and a culture of continuous learning to thrive -- at every level and across every role. It’s an imperative for organizational longevity -- and it's an even larger imperative for our learners.