During the course of the pandemic, many board leaders have asked us about the purpose and role of their Executive Committees. We couldn’t be happier about this question. It’s our view that a purposeful and well composed Executive Committee (EC) can be integral to a successful board / head partnership, a healthy board culture, and effective governance.

We know this may be counter to the prevailing wisdom: when we ask trustees why their EC operates in form but not function, the most common response is that they have been told this is best practice, designed to guard against becoming a “board within a board” and assuming power that renders the larger body of trustees ineffectual.

We certainly don’t support an all-powerful EC that functions as a “board within a board”’ But the solution to, in effect, disable the EC in order to guard against a power play strikes us as the wrong solution, designed for a misdiagnosed problem. The problem is not that ECs exist; the problem is how ECs are designed and operationalized. The key to an effective EC is its mission and membership: it relies on capable trustees who cultivate, with their head of school, shared institutional purpose and a commitment to transparency.

If we consider the Executive Committee to be a facilitating body, represented by the committee chairs and a few select trustees chosen for their perspective and capacity, we transform its purpose and function. In this conception, the EC operates as an important glue -- forging a strong communication loop between Head and Board, and distributing leadership in a way that promotes transparency, effective and efficient communications, and opportunities for meaningful learning and development among trustees. In short, the EC is a mechanism to better support your Head, develop trustees, and ensure a healthy climate and function for governance.

Portrait of a High Performing Executive Committee

A high performing Executive Committee has a clear purpose: in short, an EC should function as a facilitating and representative agent of the board, with the express purpose of ensuring strong Head support, upholding norms and standards for board engagement, promoting transparent communication, and cultivating depth and breadth of leadership.

A high-performing Executive Committee strives to achieve important benefits:

Distribution of Leadership and a Stronger School-Board Partnership: In many schools, an inactive EC is often coupled with a Board president- Head of School relationship that drives the school board partnership. There is no question that a healthy Board Chair/HOS relationship matters, but it can be enhanced and strengthened by expanding it to the EC. As a matter of fact, the risks associated with Chair-Head centric leadership are perhaps greater than those associated with an EC that operates as a “board within a board”.

By opening the circle to a well composed EC, Heads are offered better advice, broader perspective, and improved dynamics for collaboration.

Likewise, Chairs are better supported, with EC colleagues who can “pinch-hit” in times of need, and share in the efforts to facilitate the work of the board.

Improved Transparency and Coordination: an effective EC is naturally positioned to act as a facilitator and two-way feedback loop to the board’s standing committees, task forces, and individual trustees.

As issues and questions present themselves, executive committee members can initiate dialogues, with individual trustees and groups - to share information and solicit input.

Committee work can be coordinated; intersections and overlaps are identified and cross disciplinary work encouraged.

Issues the Head brings to the EC for purposes of information and/or thought partnership can be communicated to the wider board in a more transparent approach that is inclusive of all trustees.

Board Learning, Leadership Development, and Succession Planning: a strong pipeline and continuum of capable board leadership is essential to stable and effective governance, but not every school has enjoyed a long line of board leadership. In some cases, it’s because the job, whether as board or a committee leader, is viewed as undesirable. Moreover, research indicates that healthy board leadership and the longevity of a successful Head’s tenure are correlated; where we see frequent Head transitions, we often also see weakness in board leadership.

A high functioning EC is an excellent context for leadership development, offering high potential board leaders the opportunity to learn, work, and contribute around enterprise-wide matters, in active partnership with the Head.

Board Chair transitions, and committee chair positions, are well supported by EC colleagues who are ready to support and mentor new leaders. Working closely with the Governance committee, a healthy executive committee cultivates a thriving leadership pool.

Tips for Executive Committees That Work

Commitment to consistent practices and protocols can be helpful in ensuring a healthy and high functioning EC: these practices mitigate against some of the risks that have discouraged boards from activating their committees and, instead, encourage the healthy benefits we list above.

Design for Trust: Compose your committee with the chairs of your standing committees and include other trustees who bring valuable expertise, perspective and/or capacity to the Head of School. Consider and delineate what meetings can be used as a confidential and low risk environment for the Head to discuss sensitive topics or concerns, and where you might have an “open” meeting” for the purposes of transparency and information sharing. Ensure that issues that go beyond conceptualization in private meetings are properly vetted with the wider board, using the EC members as agents for agenda setting and communication.

Design for Two-Way Communications: As always, you can never over-communicate. Communications can be for the purpose of transmitting information and updates, agenda and goal setting, soliciting trustee input, and ensuring trustee engagement and support. Build a systematic process for two-way communications between the EC and the Head, and the EC and the wider board. Your approach might include regular meetings between Head and EC, with minutes that are posted to the Board portal; targeted updates by EC members to their committees and key trustees or relevant stakeholders; and regular check-ins with all trustees after board meetings or for input on critical issues. Consider how technology can assist with dialogue and confidentiality - whether via your board platform and/or other messaging and project management tools.

Design for Integration and Enterprise-Wide Governance: The EC ensures that dialogue across, within and between committees and task forces is well coordinated - helping to synthesize strategic work and facilitate effective work planning and decision-making. See our Adaptive Boards white paper for a deeper dive into committee structures that encourage strong coordination.

Design for Clarity: a well supported and high functioning EC stems from clarity of role and purpose. If you are just getting started and evolving the role of your EC, take time to work with your trustee colleagues to clearly articulate the role and function of the EC. Clarify expectations for transparency and communication, and ensure that you’ve defined the rare occasion when and under what conditions an EC might meet in private with or without the Head (for example, in cases of student or staff privacy, discipline matter, or if you are discussing a matter pertaining to head performance).

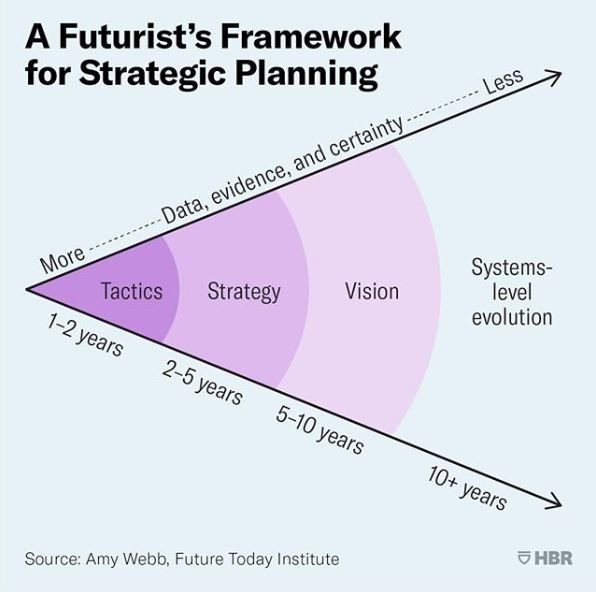

Design for Data Enriched Dialogue: EC’s function better with the right data and a forum for effective inquiry and exchange. By ensuring dialogue inside EC, there is opportunity to practice conversations, “test” issues, and collect data and input that inform a deeper dive into strategic or mission critical decisions the Board will undertake. EC’s can help a Head direct and even centralize data collection and analytics, building infrastructure for effective strategic planning, oversight, and policy development.

Don’t let old and antiquated practices hinder your ability to build and operationalize an effective Executive Committee. Every board must examine for itself what structures and practices are most valuable to effective governance, ensuring the capacity to flex and adapt as needed. An Executive Committee that can partner effectively with your Head and lead and facilitate the work of the Board is a great place to begin.