Parts One and Two of this series addressed the principles and practices of high performing teams. This final installment addresses the question of “who” – who you need, how you assess performance (of the team and each member), and what to do when you find you don’t have the right players.

Who You Need

Building a team is strategic and disciplined work. Whether you are building a board, an executive team, or a functional team, composition matters. And composition is the careful curation of mindsets, abilities, and behaviors that empower the team to be greater than any one particular member.

The first step is to decide what you need in terms of mindsets, abilities, and behaviors. No one person can fulfill all your needs, but there are certain “need to have” attributes for every member that help you build the culture and disposition of the team. You’ll likely seek evidence of collaboration skills, critical and systems thinking skills, and communication and interpersonal skills that promote productive group work. You’ll seek in each person a particular ethos and values set that mirrors the organizational ethos and honors the contributions of each team member.

Once you’ve outlined these core needs, you’ll want to seek particular functional or technical skills and expertise that round out the team – most often mapped to the areas of organizational focus and strategic choices that drive the enterprise. Don’t let the functional organization, on paper, drive the composition of your team. You may have a wider collection of senior leaders who represent the core functions and/or business lines, and you will recognize them as such, but your executive team needs to work closely with you to drive enterprise wide priorities.

For example, you may have multiple programs or divisions in your school or organization. The assumption that these leaders need to be on the executive team can be tested. You may prefer to have one leader who unifies this group and directs them in ways that ensure tight focus on institutional strategy. Similarly, you may lift up a leader, like a director of communications, who also reports to your Chief Operating Officer, to be part of your team because they exhibit both the core capacities and the particular expertise you need.

A note on who’s on the team (or in the room where it happens): as a leader, you walk the challenging line of being clear about roles and responsibilities, while also fostering inclusion, collaboration, transparency, and an authentic sense of agency and purpose in all your leaders and staff. Your executive team shares in this responsibility and together, your actions must attend to these aims.

A small executive team that works effectively can, at its best, create more space and access for robust vertical and horizontal collaboration within your organization. A CEO or Head of School with strong distributed leadership is naturally in a better position to coach, mentor, and communicate more broadly inside and outside the walls of your organization. So, work with your team to attend to communications that keep everyone in the loop . Ensure transparency and clarity about the decisions that affect your people. And work hard together to seek involvement and input from the many talented people that make it happen in your organization each day.

How to Assess

You’ve done your best work to assemble a great team – or perhaps you are working with what you inherited or have for the time being. In any case, assessment and feedback are essential tools in developing and composing the best team you can build. Too often, effective feedback and assessment are entirely overlooked, or sporadic and informal at best.

To develop and evaluate a team and its members, you want to ensure frequent reflection and feedback, coupled with more formal assessment. Talk with your team about how this work is designed – without it, the team can’t improve and you lack sound data to make good people decisions.

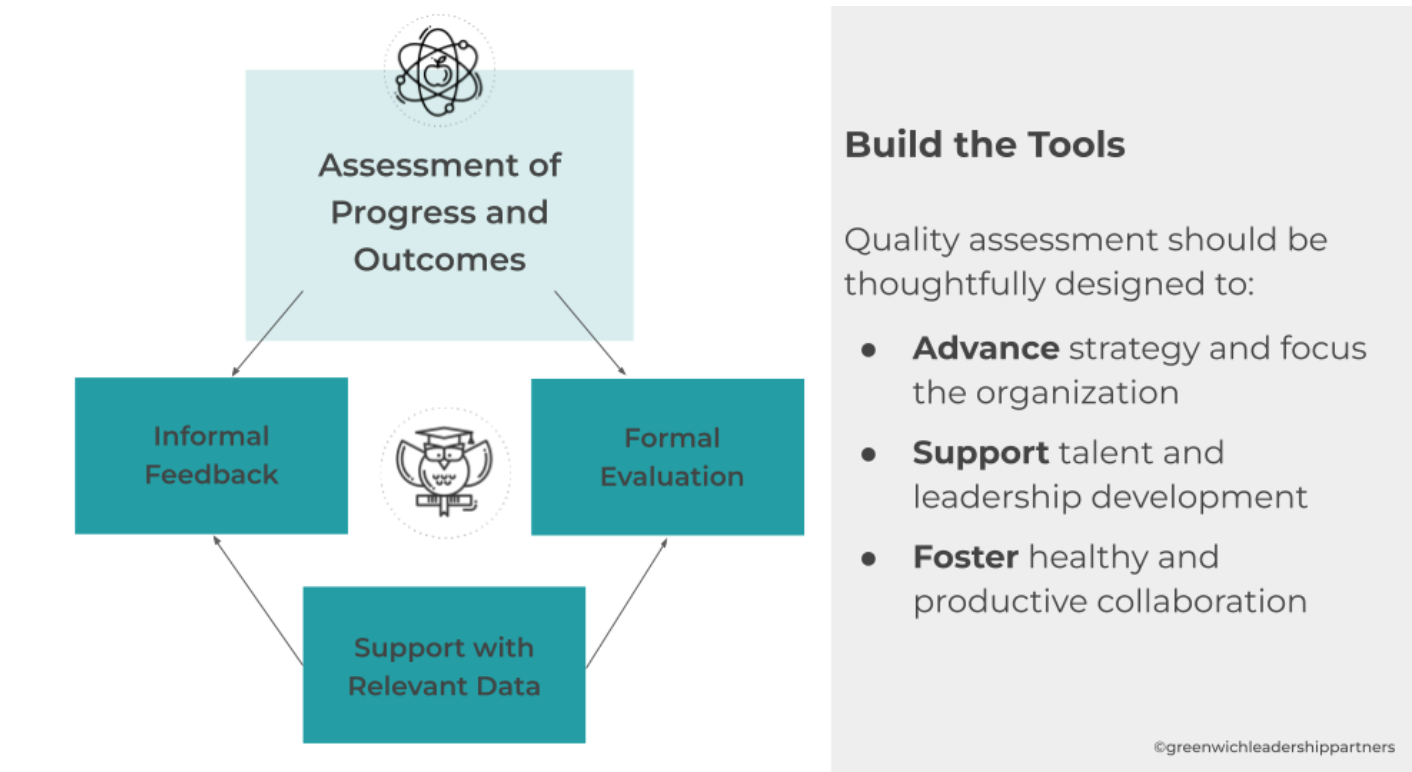

Informal and ongoing feedback stimulates correction, learning, and growth. It happens in real time, through observation and dialogue. Formal assessment is best accomplished with a thoughtfully designed tool that, in effect, measures that for which you provide informal feedback. Your team can help you build the tool, and by involving them you explore together what will drive collective performance and foster ownership for an accountability system (designing together also models how they can engage their own teams to do the same). Most good tools include assessments against the core criteria you value for team members and assessments of progress on strategic goals (see the figure below).

You’ve built criteria for team members, and your charter names areas of responsibility and key strategic goals (ideally with measures of success). Build these into your tool and update the tool annually so it works as a dynamic instrument to capture growth and development over time, and more specific performance on organizational goals. Remember to use clearly stated scaled and open-ended queries that assess both the function of the individual and the function of the team as a whole.

Engage the right people in the process of assessment: if you limit formal evaluation to your own perspective, you lose valuable insight and perspective on both individual and team performance. Who might have experiences, observations, and insight that help you assess? Consider peers, direct reports, and collaborators when you administer formal assessment. We prefer to steer away from terms like “360 degree review” which often implies wide scale feedback - sometimes from the whole organization. What we do encourage is that you solicit thoughtful feedback from people who interact directly with members of the team and witness their leadership.

When You Don’t Have the Right Talent

Sometimes you inherit a team member who just doesn’t want to play by the values and norms you’ve established, and sometimes these folks are toxic to the team. Or, despite your best efforts, you’ve discovered that the person you are coaching is not likely to master the capabilities you need, and while well-liked, frustration within the team is mounting. Maybe you have an open position or an emerging gap and you need to fill it – and until you do everyone is working harder, but not smarter. Know that the team is never static, and you will likely be dealing with one or more of these realities often, if not all the time, in the course of your leadership.

If you have a player that needs to be moved off the team, but you are not sure how or when to do so, the most important thing to ask is:

How is this individual’s performance

impacting the people who lead us forward?

In the effort and time it takes to figure out how and when to move on a poor performer, we often lose sight of how that person is impacting others over time – and we delay the hard decision or construct unsustainable workarounds. Often, leaders underestimate the cost to the team, so if there’s one thing to remember it’s this:

Preserve optimism and energy in the people who will lead you forward

by acting humanely and decisively on the people who cannot.

If you have attended to feedback and assessment purposefully, your job is made easier. If not, you’ll need to work quickly, with the right support, to either remove or redirect a player in order to protect the morale and focus of your team. If this person is harming team culture or breeding real frustration, delay is costly, and too often we see leaders who prioritize their concerns for that individual over the needs of the team. In the end, no one is better off.

Leaders need partners who can help them address these talent issues. Who helps you? Not-for-profit and school organizations often lack in-house strategic human resource leaders to advise them, and if this is you, make sure you have an external resource to guide you. But remember, the hard part is taking decisive action – once you decide, the tactics will follow.

Finally, if you have a gap in your team and need to fill it, you may look both within and without your organization for talent. The key here is twofold:

Do this with your team: develop a shared understanding of what you need and the profile for the role. Involve your team in the interview process, and agree on decision-making criteria.

Be accountable to a timeline: the long, dragged out processes to find the perfect person can really bring your team down. Find the person most likely to “fit” and “grow” – don’t expect perfect. And have a back up plan (perhaps outsourced or attended to by a junior “interim” team inside your organization). Know your best alternative to a great hire and implement it early, so that if things don’t pan out in your first efforts, you know what to do in the interim.

In the end, knowing you have a team and coaching it to success is never-ending work! Teams, like organizations and people, are living organisms that need to continuously learn, evolve and adapt. As a leader, your attention to the health and function of the team is one of your primary responsibilities. Let us know if we can help!