Following our interview with Charles Fadel, we found ourselves examining the many questions schools need to confront if they are to thrive in conditions that are less than predictable and often highly volatile. Practically speaking, how do schools stay ahead of problems, navigate the unexpected, and sustain real progress? Before we get deep into school design, pedagogy, and curriculum questions, we think schools have to recenter themselves in purpose with ever more clarity and precision.

What is the purpose of school in the volatile context of the social, political, and economic forces at play and their ripple effects in our educational communities?

Worried about the 2024 election? Free speech? Hot war? Cold War? Social unrest? Mental health? Social media and screens? AI? The quest for talent? Are you wondering if your board and your community are prepared to weather the storms and their aftermath? How do we navigate these issues in service of students and guard against the currents that take our schools off course?

Not surprisingly, we’ve witnessed a significant uptick in boards who want to sharpen their systems, structures, and practices in hopes of managing risk and becoming more resilient. We embrace the arrival of a new era for governance, and our position is that much of the conventional wisdom offered to NFP boards is outdated, reductionist, and inadequate in the face of so much complexity. We hear trustees asking “Can’t we do better?” and leaders who are trying to understand how to engage their boards in new and constructive ways. We also understand that there are counter forces: resistance to change, structural limitations, external pressures, and economic realities to name a few.

In order to improve the work of your board, there is a foundational first step: recommitting to, affirming, or recalibrating your mission.

Mission is often taken for granted—and it goes unexamined. Do you have an actionable, clear mission that truly shapes the daily life of the school? Living the mission is nuanced, complex, and challenging. Having clarity of mission and values provides common ground for your school community in a world of increasing fragmentation, polarization, and turmoil. It also means that when challenges arise (in your inbox, the news, or on campus), your community is able to navigate the small and big decisions in ways that move you forward rather than derailing progress and detracting from learning.

Leaders can direct and guide their boards, but ultimately the question of purpose—and the alignment of the organization’s actions to its mission and values—is an essential responsibility of the board.

So we begin here: Grounding ourselves in the question of the purpose of education is essential context for the associated question of how leadership and boards create conditions for success.

Confidence in Purpose

It’s hard to prepare for the future when so many of our institutions face a crisis of confidence. Higher ed and public education are often a harbinger for issues faced by independent schools, so we offer some perspectives on public sentiment. Gallup’s 2023 research in higher education shows American confidence since 2015, across Republicans, Independents, and Democrats, is declining and tracks fairly closely to what we see in the public K-12 sector.

Today, college campuses are navigating complex questions about free speech, free assembly, and protest. The public questions safety and wonders why students are not in classrooms. Independent schools may have retained more confidence but are not immune to criticism and controversy.

At the macro-level, David Brooks addressed this trend in 2020, and his insight is still relevant: when trust collapses, the threat to society is “existential.” In other words, confidence in and openness to each other and to our institutions matters—and if we can’t create or sustain it, we are in trouble.

So as colleges close abruptly and students question the value of a college degree, confidence in schools and universities is also eroding—on the inside and the outside. In some cases, jurisdictions are taking hold (Florida is the most visible example), and in private schools, leaders are playing whack-a-mole as they respond to critiques, concerns, and questions about everything from their policies (from gender to mental health to discipline), DEI programs, responses to national or global events, and to foundational standards in their curriculum.

In this climate of widespread tension, it is more important than ever to preserve and restore confidence in education. Our schools are essential to building a healthy society—in which we prepare ethical citizens with the skills and knowledge to think critically, sustain themselves and their families, and contribute to their communities.

How’d We Get Here?

We think it’s helpful to examine the changes in climate and the breakdown of confidence in our institutions through the lenses of free speech, freedom of expression, and academic freedom. One only needs to read the news to know that even our most venerated educational institutions are at risk. These unfolding stories offer object lessons in how easily and quickly a seemingly strong, well-protected educational environment can come under significant duress—and raise fundamental questions about the purpose of school and the responsibilities of governance and leadership.

Understanding where we are may begin with a widening of our apertures as we return to the primary mission of education. In a worthwhile and wide-ranging podcast interview, Larry Summers observes and articulates what we’ve mused about for a long time:

“I think one of the aspects of how this has happened is that while on the one hand we think of intellectual communities as being the most broad-minded of communities, on the other hand they are actually among the most narrow, insular and inward-looking in the way they evaluate themselves and in the way they think of the necessary decision making.”

He continues, with more precision—with a particular focus on governing boards:

"I think, unfortunately, with considerable validity—that many of our leading universities have lost their way; that values that one associated as central to universities—excellence, truth, integrity, opportunity—have come to seem like secondary values relative to the pursuit of certain concepts of social justice, the veneration of certain concepts of identity, the primacy of feeling over analysis, and the elevation of subjective perspective. And that has led to clashes within universities and, more importantly, an enormous estrangement between universities and the broader society."

Some of our educational communities are here, in part, because boards and leaders took their eyes off the most fundamental idea: that the purpose of school is to broadly educate, to pursue knowledge and truth, and to model the way for a civil society with relentless inquiry, evidence-based reasoning, open and respectful discourse, and rigorous scholarship. The school’s intellectual purpose is primary—and it is in service of social good

Even if an educational community has managed to keep their eyes on mission and values, what it means to live the mission each day is dramatically harder due to the surrounding societal and technological changes.

Nuance doesn’t go viral. With social media, everyone has a microphone, and conflict is what draws attention. The loudest, most emphatic voices can hijack a school’s focus. As Ben Sasse observes for higher ed, “Instead of drawing the line in speech and action, a lot of universities bizarrely give the most attention and most voice to the smallest, angriest group.” We see this reality play out, in response to a variety of issues and demands, in our k-12 schools.

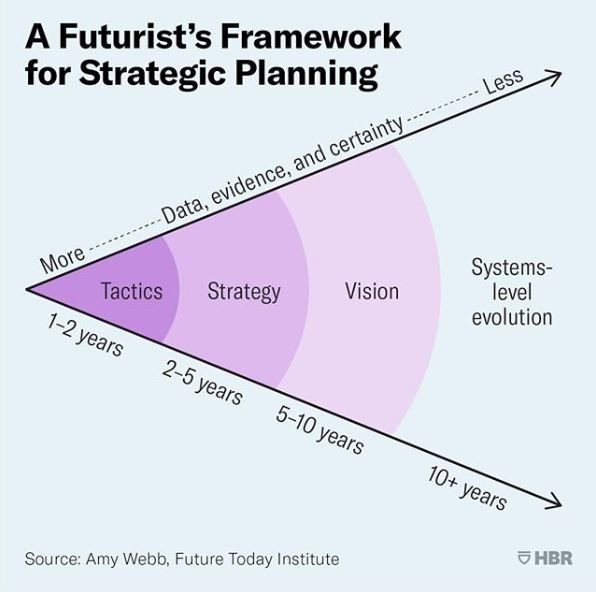

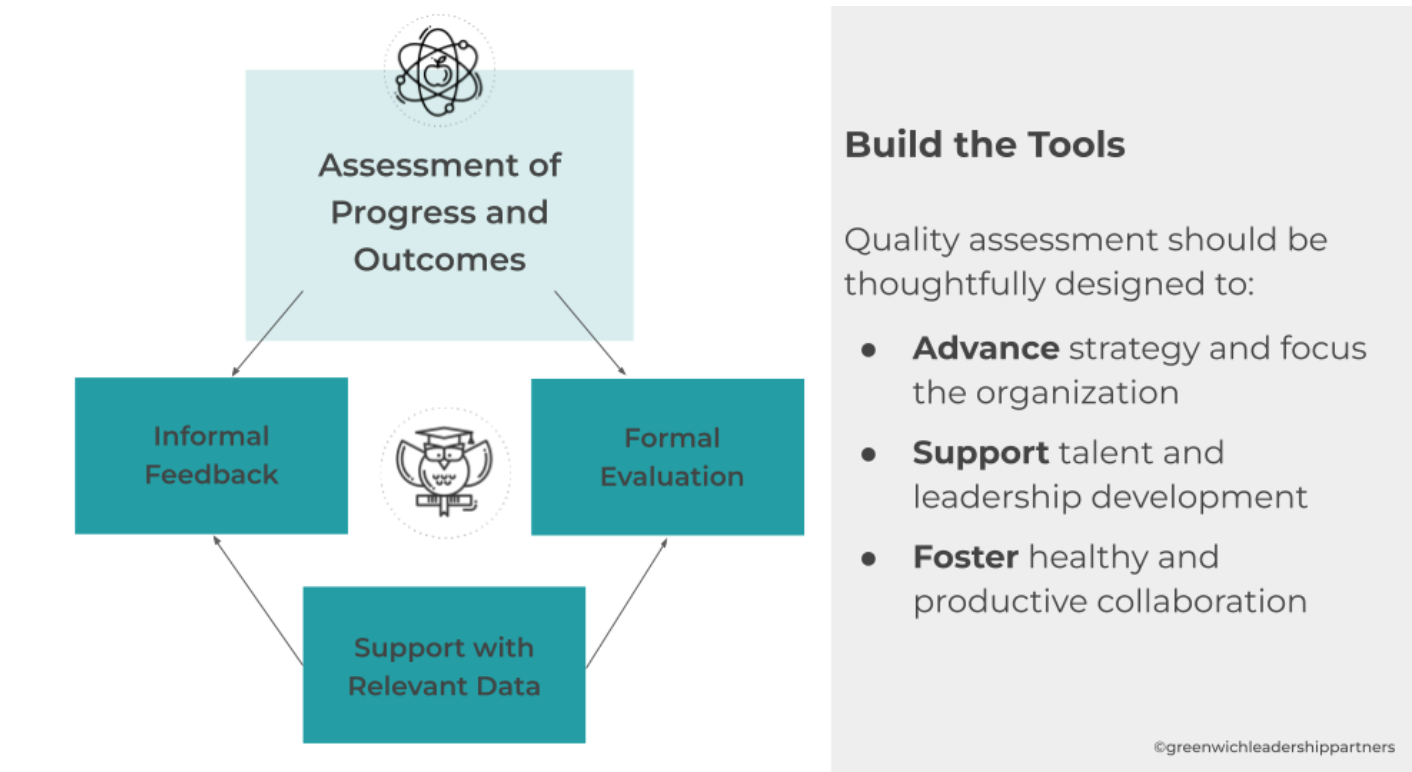

Schools can and should survive these storms. When boards and leadership are sustained by ample resources, strong institutional memory, sage advice, and a desire to work in partnership, the opportunity for growth and improvement is ripe. Future-focused boards and leadership are taking stock, and sharpening their efforts to affirm their missions, align their choices, assess the student outcomes and experiences that matter most, and strengthen the structures and practices that drive them.

Governance and leadership must align actions to values

Private and public K-12 schools may have escaped some of the heat, but a great many are in or have experienced some version of community controversy over what to say, and how to educate, and what identity or group to publicly support. The strategy for handling these questions seems simple: respond, communicate, and decide in alignment with mission and values. However, not every school espouses, or clarifies, their mission or values with precision. Additionally, it is the execution that becomes a lot more complicated—even for a school with a clear mission.

Every decision and practice is a manifestation of mission and values.

Pressure comes from countless constituents (often segmented in small but highly vocal numbers): high profile donors, passionate faculty members with strong ideas about what to cultivate in learners, concerned parents who feel usurped by decisions implemented in classroom curricula, and boards who have never had to interrogate decisions and controversies related to the core: why, how, and what to teach.

At the highest level, much of the controversy can find roots in the “stance” of the institution, and how that plays out inside the classroom and in the larger learning community. Regarding higher ed, the Kalven Report reminds us that colleges are not critics—they are “the home and sponsor of critics.” Sage advice for our K-12 schools who lay the foundation for educating young people to become constructive and wise critics!

When a university itself takes a position on political debates, the report says it risks being “diverted from its mission into playing the role of a second-rate political force or influence.”

Words matter a lot, and that’s where the arguments begin. Definitions for the concepts of academic freedom, free speech, and free expression—and ways in which we uphold free speech and expressio n in service of mission – also bear examination. As this essay from the Provost at the University of Austin points out, it’s easy to conflate and/or confuse these ideas, and that can lead our educational institutions off the path of mission–making the case simple with this statement:

“But at universities, the right to free speech stops when speech impedes higher education's essential calling: the pursuit of truth so as to preserve, transmit, and extend knowledge.”

In these perspectives, we see that free inquiry, speech, protest, and pursuit of truth are not in conflict–provided they advance rather than inhibit these aims for all. This central idea requires extraordinary clarity and consistency in mission-aligned policy and practice—and it might be the one central idea that will help our boards confirm and guard mission, and determine how to assess fidelity to and delivery of that mission.

Navigating the details - the realities of how everyday choices and actions align to mission - is where a strong, open, and transparent understanding between board and leadership comes to bear. The best governing boards and heads understand how these small choices serve or do not serve mission and values—and strong leaders engage their boards in robust dialogue about how mission delivery happens, upholding culture and purpose.

What Next?

K-12 schools—like colleges and universities—have community members who wish for us to act as a political force or influence. This works if everyone shares the same opinion about what that force or influence means, or what ideas undergird it, but in the absence of strong shared principles about how to engage with these differences, taking a particular stance is a misguided activity. Learning—and education—is the exploration of these viewpoints, arguments, and rationales, supported with research, evidence, and strong reasoning. Affording space for rigorous inquiry is the principle, and getting back to basics is the best means to assert and restore mission. We appreciate the work of author John Austin of Deerfield Academy, and the EE Ford Foundation for this framework to guide independent schools and a reminder that:

“Schools exist to serve students, and meeting their needs must come first. Further, providing the foundation for students to think for themselves, test their views, and empower them to ‘grow into distinct thinking individuals’ is a worthy aspiration for every school, regardless of its mission.”

We hope you will share your perspectives, arguments, insights, questions, and suggestions with us!