By Cara Gallagher, Director of Thought Leadership, Associate Director of Qualitative Research, Consultant

Are we Facing a Teaching Talent Crisis? GLP weighs in on the national dialogue.

Last summer was the first time this question came on my radar. Someone forwarded me a Twitter post about a group on Facebook called “Leave Teaching…And Smile :-).” Curious, I discovered that not only did it exist, it had over ten thousand members (it currently has 14,000). A quick search of the word “teaching” in the groups section of Facebook surfaced at least five whose sole charge is to help teachers leave the field. One group called “Life After Teaching - Exit the Classroom and Thrive” has 81,000 members and functions both as a one-stop shop where burnt out teachers can get emotional support, peruse jobs posted by other members, and connect with transitional career counselors and resumé coaches.

This trend is not unique to primary and secondary education. Academics in higher education are feeling the same strains and taking their frustrations to Facebook. One group called “The Professor Is Out” – created only a year ago and already has 24,000+ members – was created to help tenured professors leave higher education. Subreddit group r/Professors has 100,000 members and offers “a place for professors to BS with each other, share professional concerns, get advice and encouragement, vent (oh, especially that), and share memes.”

Teachers Leaving is not a “New” Problem

What strikes me is that most of these groups were created before the pandemic. Interestingly, many were formed in 2018 or 2019, immediately before Covid started. This certainly challenges the prevailing narrative that Covid caused teachers to flee classrooms for different careers. While the formation of these Facebook groups may have begun before the pandemic, it’s fair to assume burnout and job fatigue were underlying conditions that Covid may have worsened at an accelerated rate.

So our answer to the question about whether or not we have a talent crisis is “Yes, and no.”

Context… a Slow Burn, and Conflicting Data

The teacher shortage is more than a decade in the making: Remember that the field historically has always had a higher turnover rate than others. Thirty percent of educators leave the field within 6 years of entering it. After secretaries, childcare workers, paralegals, and correctional officers, teachers have the fifth highest turnover rate by occupation.

In November, the Wall Street Journal published an article about quit rates across different sectors. One data point that was particularly troubling was that “quits in the education sector—which accounts for a larger share of employment in Northeastern states than many others—have risen at the fastest pace of any industry since January (2021).” In May of 2021, the National Department of Labor reported public education employment dropped to levels not seen since August of 2000.

These two points, combined with a reality that the pipeline of teachers entering education training programs has been in a steady decline since 2010, raise some concerns; however, what they don’t take into consideration is the degree to which Covid has adversely impacted the teacher workforce.

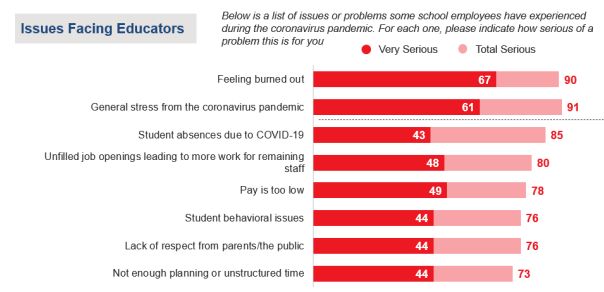

New research gives us a glimpse of how Covid may be disrupting both the current and future teacher labor market. According to American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE) member surveys, in 2021 and 2022 about 20% of institutions reported a decline in new undergraduate enrollment of 11% or more; 19% of undergraduate-level and 11% of graduate-level teaching programs saw a significant drop in enrollment this year. Additionally, in February, the NEA published an alarming report that “55 percent of educators are thinking about leaving the profession earlier than they had planned.” This is an 18% jump from when teachers were asked about their likelihood of leaving last August and takes into account factors such as their age, years of service, proximity to retirement, role at the school and impact on children.

But talking about leaving is not the same as leaving: Chad Aldeman, a researcher at Georgetown’s Edunomics Lab who studies public education policy and the teacher labor market, recently found “the [teacher] quit rate has held at lower or average rates during the pandemic. But here’s the thing, openings are way outpacing hiring right now, and that’s partially thanks to the big infusion of federal funding that’s created the opportunity to hire more people, and that’s leading to a higher vacancy rate.” Aldeman also points out “voluntary ‘quit’ rates were slightly above the 20-year average, while ‘total separations’ that include quits, layoffs and retirements were slightly below average. State-level data for teachers shows that turnover has remained on par with long-term historical trends.” With that said, Alderman is cautiously optimistic. “The story of next year has yet to be told,” he said.

To compare public school data with independent and private schools, NAIS Career Center looked at monthly job postings before and during the pandemic to see what if any impact Covid had. “Because of the traditional contract renewal schedule, the peak job posting activity usually occurs in March and April. If we consider 2019 as a representative pre-pandemic year and compare the job postings to 2021, we see that, after a delayed start, the number of jobs posted were consistently and significantly higher than the pre-pandemic patterns. Even more troubling is what we are seeing for this year. The number of job postings in 2022 is even higher. Overall, the number of new jobs posted to the Career Center in the first three months of 2022 is 59% higher than in 2021.”

According to NAIS, “clearly the fact that the number of job postings is so high relative to historical data is an indicator that schools are facing hiring pain.”

Another troubling data point is that there was a 12% decline in the number of job seekers looking at openings posted to NAIS job center database.

Conditions, Perceptions, and the Problem

When the data conflict, we are left with no conclusions and the news cycle coupled with anecdotal observations fill the vacuum. And as we know: Perception is one version of reality.

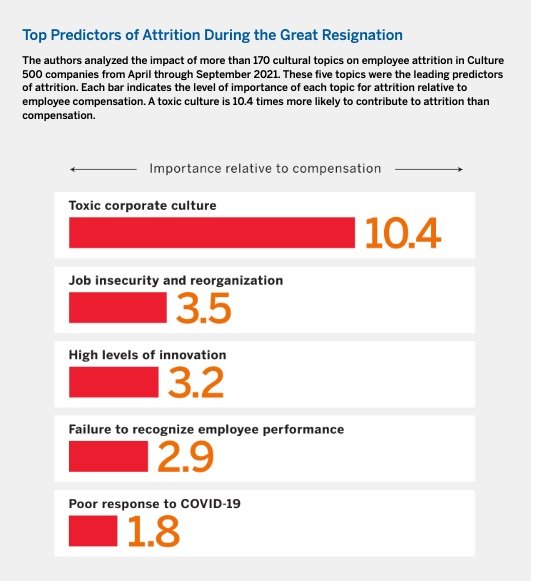

But if it feels like teachers are fleeing schools as part of this phenomenon we’re calling “The Great Resignation,” there’s probably some truth to that. The reality is that teachers – like everyone else during the pandemic – took stock and reevaluated their lives, jobs, and futures. They looked around and saw school boards shouting over what they could and couldn’t teach, how to be healthy and safe, and whether or not they were “essential”. Teachers switched up their lesson plans for in-person, hybrid, and/or online learning on a moment’s notice and endured an endless stream of thundering emails, opinions, and national debates about whether or not kids should stay home, learn online, go back in person, and wear a mask. As these challenges continued through the end of the 2020 school year and settled into the next two years, so did symptoms like fatigue and burnout.

Some educators realized they wanted the same freedoms afforded to those who worked from home since the start of the pandemic. The decreased responsibilities and an ability to find more separation or balance in their personal lives and their jobs appealed to them. As one member of the Facebook group “The Professor Is Out” put it, “The pandemic really exposed the cracks in the foundation and made people realize that this is not a healthy way to live. And I think that that was a wake-up call, sort of across the entire industry, that there's other options out there.”

The exact percentage of teachers that have left the field due to these “pull” factors might not be possible to gather data on for a while. It hasn’t been long enough to collect data and draw any concrete conclusions. With that said, can schools afford to wait to find out if this is or isn’t going to be a mild headache versus a full blown crisis?

No, they can’t. The simple truth is that if educators are leaving the field and the pool of applicants is eroding, you have to take steps immediately to 1) understand the problem within your school or system and 2) develop fresh approaches to how you recruit and retain your current talent.

Stay tuned! We’ll offer some concrete suggestions in our next blog and welcome your comments and insights as we finalize the next post.